Was Kentucky’s Abraham Lincoln An Evil Racist?

Thomas McAdam

iLocalNews Louisville is your best source of news and information about Derby City.

- Professional Journalist

Your iLocalNews reporter lives with his family in a modest house on Wickland Road; located in the middle of what used to be an ante-bellum slave plantation known as Hayfield. The nearest neighbors to Hayfield were the slave plantations of Bashford Manor, to the South, and Farmington, to the East. In the Summer of 1841, a young lawyer from Illinois named Abraham Lincoln stayed at Farmington with its owner, Lincoln’s old friend and former business partner, Joshua Speed.

In their almost daily horseback rides around the neighborhood, Josh and Abe would certainly have ridden along what is now Wickland Road, and doubtless would have stopped for a cool drink at Hayfield’s springhouse; located on the exact spot where our home now stands. More than likely, the dipper of cool spring water would have been handed up to the future president by the hands of one of Hayfield’s Negro slaves.

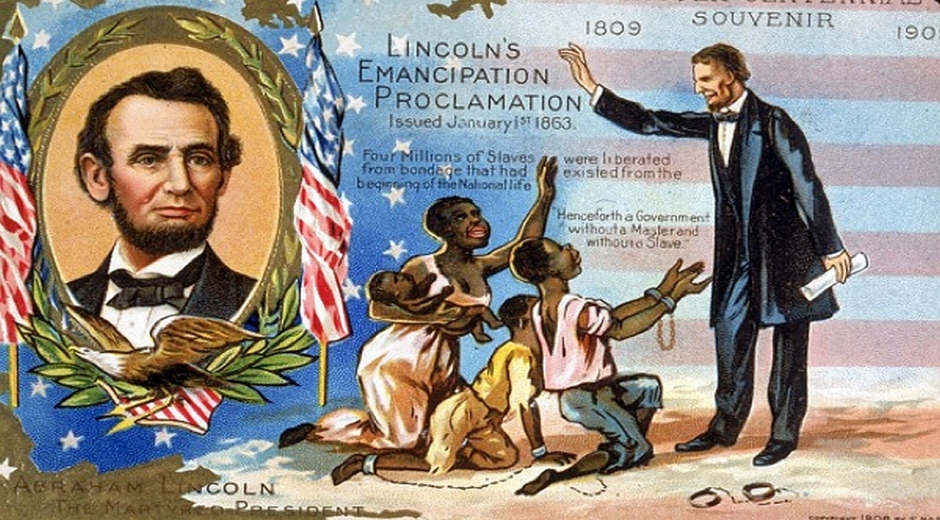

So, since last Friday was the 207th anniversary of Lincoln’s birth, it may be fitting for us to look back upon the life and pronouncements of our 16th president. The Great Emancipator? Defender of the Union? Racist warmonger? Bloodthirsty tyrant? You be the judge.

There is, we submit, no more egregious example of revisionist history than the lies we tell our children about Abraham Lincoln. The mythology surrounding his tyrannical leadership of the Union during its ------ invasion of the Confederacy tends to paint him as something of a saint; when in reality, he was among the cruelest oppressors of modern times.

Lincoln sent an army into the Confederacy, with instructions to burn, pillage, and destroy the Southern economy. This war resulted in the deaths of more than 600,000 Americans; many of them civilians. He suspended civil liberties in the North, including the writ of habeas corpus, and filled the jails with more than 13,000 political prisoners; all incarcerated without due process. When the Supreme Court ordered him to release some of these illegally-held citizens, Lincoln simply ignored the court’s order.

Most historians prefer to ignore Abraham Lincoln’s views on slavery and race, but any fair appraisal of his public statements on those topics cannot fail to show him to be an uncompromising white supremacist. During his 1858 campaign against Steven Douglas for the U.S. Senate, Lincoln gave a speech on September 18 in which he made his position clear: “I am not, nor ever have been in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races; I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of Negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor intermarry with white people. I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality.”

Lincoln explained his proposed solution to the problem of slavery in America during a speech in Springfield, Illinois, in 1857: “There is a natural disgust in the minds of nearly all white people to the idea of an indiscriminate amalgamation of the white and black races. A separation of the races is the only prevention of amalgamation ... Such separation ... must be effected by colonization ... The enterprise is a difficult one, but where there is a will there is a way, and what colonization needs now is a hearty will. Let us be brought to believe it is morally right to transfer the African to his native clime, and we shall find a way to do it, however great the task may be.”

On August 14, 1862, President Lincoln invited a delegation of free Blacks to the White House. He spoke to them and said: “You and we are different races. We have between us a broader difference than exists between almost any two races ... [T]his physical difference is a great disadvantage to us both, as I think your race suffers very greatly, many of them, by living among us, while ours suffers from your presence. It is better for us both, therefore, to be separated,” he concluded, and urged the delegation to find men who were willing to move, with their families, to a colony he planned to set up in Central America. On September 12, 1862, five days before Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, the federal government signed a contract for colonization on land in Panama. The contract included a signed statement from the President directing the Secretary of the Interior to execute the contract. The very day before issuing the Proclamation, Lincoln signed a contract for the resettlement of 5,000 free Blacks on an Island near Haiti. Tragically, the contractor turned out to be a cruel swindler, who rounded up several hundred ex-slaves and left them on an uninhabited island, where most of them died.

In his message to Congress on December 1, 1862, Lincoln talked about his Negro resettlement plan: “That portion of the earth’s surface which is owned and inhabited by the people of the United States is well adapted to be the home of one national family; and it is not well adapted for two, or more. I have urged colonization of the Negroes, and I shall continue. My Emancipation Proclamation was linked with this plan ... I can conceive of no greater calamity than the assimilation of the Negro into our social and political life as our equal ... We cannot attain the ideal union our Fathers dreamed, with millions of an alien, inferior race among us, whose assimilation is neither possible or desirable.” He went on to propose an amendment to the Constitution that would give Congress the power to appropriate money and send free Blacks, with their consent, to places outside of the United States

General Benjamin Butler reported a conversation with the President in early April of 1865, by which time the war had been won and Lincoln’s assassination was only a few days away. Lincoln said to him, “But what shall we do with the Negroes after they are free? I can scarcely believe that the South and the North can live in peace, unless we can get rid of the Negroes.”

When he shot President Lincoln in the back of the head at Ford’s Theatre, John Wilkes Booth jumped onto the stage and shouted: “Sic Semper Tyrranis!” He was quoting what Shakespeare’s Brutus said, upon stabbing Julius Caesar: “Thus always to tyrants!”

Happy birthday, Abe. You are still welcome to stop by the house for a cool drink of water. Maybe we could stroll over to the intersection of Bardstown Road and Trevellian Way, and I can show you where your Yankee soldiers hid behind a wall up where McDonald's golden arches are now; firing down upon some of Morgan's Raiders, who were standing over by the SubWay sandwich shop. Don't worry, we cleaned up all the blood years ago. You may be a little disappointed, however, when you learn that the neighborhood is now racially integrated.

Read more: Was Lincoln a Tyrant? by Thomas J. DiLorenzo

Read more: Abraham Lincoln: Liar, Racist, Tyrant.

Read more: Was Lincoln a Racist? by Henry Louis Gates Jr.

Read more: Was Lincoln a Racist? by Jack E. White, TIME magazine